By Ari Weinzweig

The Roadhouse’s 219th Special Dinner will be the thirteenth of this special series that have, very appropriately and importantly, honored the foodways of the African American culinary community. This year’s dinner has come together in particularly fun and inspiring ways.

Each of these special dinners is, of course, not “just another meal.” We try, with each event to make the meal educational as well as offering good eating. Over the years we’ve covered cooking from pretty much every region, from dozens of the cultures and cuisines that come together to make up what I call “American cooking.” This year we bring together a special menu—the foods of the late and great chef and writer Edna Lewis, and a tribute to the work of African American wine-makers, represented for this evening by the rather remarkable, witty, and very skilled André Hueston Mack and his Oregon winery, Maison Noir.

Insight and Identity

While pieces of who we are may overlap, patterns may seem pro-found, and cultural continuity within a community can count for a lot, at the end of the day we’re all really just ourselves—a unique combination of complexities that come together in our hearts, our souls, our minds and our bodies.

Just as mono-cropping isn’t sustainable in the agricultural ecosystem, I’ve begun to believe with ever greater strength the diversity we desire in society is all the more likely to work when we embrace our own diversity from within. As M. Maalouf writes,“I haven’t got several identities: I’ve got just one, made up of many components in a mixture that is unique to me, just as other people’s identity is unique to them as individuals.” I agree. My work in life, I’ve come to believe, is to seek out that unique-ness, and to work my tail off to honor it in every human being I come in contact with. Whether I like them or not isn’t really all that relevant. My assignment to myself, my challenge, my inquiry, my art…is to find the artist in them. “Every individual,” Maalouf makes clear, “is a meeting ground for many different allegiances, and sometimes these loyalties conflict with one another and confront the person who harbours them with difficult choices.”

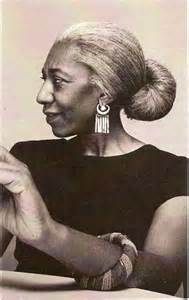

The key is to honor the uniqueness of the individual and, within that framework, the communities with which they choose to be connected. I say all this because on January 30th we will convene at the Roadhouse for our 13th annual African American foodways dinner. We’ll feature and honor the work of two amazing individuals, interesting and important contributors to an exceptional community. One of the two, Edna Lewis, is a special part of African American culinary history, who sadly passed away a decade ago. Her work inspires me, and I know many others, to this day.

The other guest for the evening, André Hueston Mack, is in the prime of his life, a marvelous African American winemaker, entrepreneur, award-winning sommelier and designer. Both he and Miss Lewis have contributed creatively and significantly to African American—and hence, it’s important to note, American—culture. And yet both are far more interesting than their titles would ever let on. Neither fits the standard, socially-imposed molds. Both are amazing, inspiring individuals who live and lived life in their own, authentic, individual, one of a kind way. Both I would argue, are living Thelonious Monk’s super marvelous statement, “A genius is the one most like himself.” These two, in their own way, qualifies. With honors.

Through them, my hope is that this dinner is a chance to honor the complex, creative contributions of the African American community, in particular, through the work of two wonderful individuals.

Ed Catmull, co-founder of Pixar, posited that there “is a fundamental misunderstanding of art on the part of most people. Because they think of art as learning to draw or learning a certain kind of self-expression. But in fact, what artists do is they learn to see.” Edna Lewis saw very clearly, elegantly and eloquently, with her own two eyes a particular perspective on the world of food and cooking. She also helped me see. Her African American food, her Southern food, her American food is something special, something different from what so much of the world would tell you. It’s inspiring. Great. Graceful. As New York Times writer Kim Severson said, “I didn’t know how much I didn’t know about Southern cooking until I started reading what Miss Lewis had written.”

I wish I’d met Edna Lewis in person. From what I’ve read and heard from friends, she was an exceptional woman. John T. Edge, director of the Southern Foodways Alliance, shared that, “Long before the term came into common parlance, Edna Lewis advocated for what we now call farm-to-table cookery. Her lyrical writing and honest palate proved models for the movement that surfed her wake.” Writer Francis Lam wrote, “Lewis took the story of rural black people, formerly enslaved black people, and owned it as a story of confidence and beauty. She didn’t have an easy life, even in her Freetown years. Her family suffered through two stillborn children and two more who died young of pneumonia. But she chose to see, and to show us, beauty; and under the shadow of oppression and slavery, that is a political act.” And an inspiring one in which she made a meaningful difference for many. Kim Severson said, “Politics were very important to Miss Lewis. She had been the first in her family to vote, and said her greatest honor was to work for Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first presidential race. Later, she would march with Dr. Martin Luther King at the Poor People’s March on Washington in 1968.” Lewis was not in the least naïve to the social struggles, or to what it meant to be African American in the 20th century, or for that matter, still today in the 21st. She was very much an activist. “When I first came to New York just before World War II,” she wrote, “I joined the communist party. They were the only ones encouraging the blacks to be aggressive. To participate.” Francis Lam writes that, “Lewis’s niece, her youngest sister Naomi’s daughter, Nina Williams-Mbengue, who, at age 12, took her aunt’s handwritten sheets of yellow legal-pad paper and typed the manuscript for The Taste of Country Cooking. Her aunt never said her book was meant to be political. But she often spoke of being inspired by the people and the humane, communal spirit of Freetown. Williams-Mbengue said: ‘‘She just didn’t have any notion that these people were less-than because they were poor farming people. She wanted to make their lives count.’’ And then she added: ‘‘Imagine being enslaved, then rising above that to build your own town. Aunt Edna was always amazed that one of the first things they did was to plant orchards, so that their children would see the fruit of their efforts. How could those communities have such a gift? Was it that the future had to be so bright because they knew the past that they were coming out of?’’ From everything I’ve read, heard and understood, Edna Lewis was a lovely soul, one that the rest of us can aspire and admire, even if we never had the chance to get to know her in person.

Best as I can tell, she and I had completely opposite culinary backgrounds. Lewis grew up the granddaughter of slaves in Freetown, in rural Virginia; I grew up the grandson of Jewish immigrants on the streets of Chicago. Edna Lewis wrote that, “When I was a girl, we ate fish only when it was caught in a nearby stream, lake or river.” I was raised on Mrs. Paul’s fish sticks pan-fried in margarine. As a child she and her siblings regularly went to the woods to pick wild berries; I grew up going to the supermarket hunting down boxes of my favorite breakfast cereal. Lewis writes lovingly about ash cakes (corn cakes baked in the ashes); I have fond memories of walking on hot asphalt. Granted, my grandmother did make roast chicken every Friday night for the Sabbath meal but given that we kept kosher I can tell you it was never like it was for Ms. Lewis—her family supped on skillet-fried chicken cooked in a mix of leaf lard and freshly churned butter seasoned with a slice of long smoked country ham. Amin Maalouf wrote in his book, In the Name of Identity, that, “each of us has two heritages, a ‘vertical’ one that comes to us from our ancestors, our religious community and our popular traditions, and a ‘horizontal’ one transmitted to us by our contemporaries and by the age we live in.” In that sense, Edna Lewis and I clearly had completely different vertical heritages. And yet, our horizontal heritage, have a very high degree of overlap. We share a set of very similar beliefs. About food. About cooking. About culture. About people. About life. The food philosophies she learned as a child are the ones that I came to learn as an adult working my way through the food business. I’m not all that big on heroes, but if you have to have one, you don’t do much better than to elevate Edna Lewis. Here’s a bit of Lewis’ philosophy in her own words:

“I learned about cooking and flavor as a child, watching my mother prepare food in our kitchen in Virginia…Living in a rural area gave my mother the chance to cook food soon after it was picked. I just naturally followed her example. In those days, we lived by the seasons, and I quickly discovered that food tastes best when it is naturally ripe and ready to eat. As a result, I believe I know how food should taste.”

“One of the greatest pleasures of my life has been that I never stopped learning about good cooking and good food. Some of the recipes here are old friends, others are new discoveries. All represent a lifetime spent in the pursuit of good flavor.”

“If you eat a vegetable when it has been grown under all the right conditions, including reaching maturity at the right time of year, it tastes as good as it can be. I think it is important to keep this in mind—which is why I’m so delighted that so many cities have established farmers’ markets where local farmers can sell their produce.”

“…Wild things never fail us. They always taste good, which is why if you see only a handful of wild nuts or a cupful of berries, you should pick them. They have a flavor nothing else has. If you transplant a wild plant to the garden it will never taste the same.”

“I think the cheese tasted so good because of the tender grass in the fields where the dairy cows grazed.”

“These meats might cost more, but as with all good-tasting things, you may not need as much—the honest flavor compensates for the quantity.”

Edna Lewis’ loving approaches to nature and food are very much aligned with how we work with food here at Zingerman’s. You only need to read a small bit of her work to know that Ms. Lewis knew the seasons, she knew nature, she knew herself. I hope that I can get even halfway to what she knew.

Cooking Edna Lewis’ food at the Roadhouse, Head Chef Bob Bennett, who’s been at the Roadhouse since we opened the restaurant in 2003, shares a lot of these same beliefs about food and cooking. Bob shared: “I like Edna Lewis for a lot of reasons. Three things stand out that hit home for me. The first being the simplicity of the food, from the raising of it, through to the way it’s cooked. There is a certain air of ‘this is how real food is made’—it’s a style of cooking where the products do all the talking. The second thing is the sense of community and family that comes through. All her food is gathering food. It’s the food you want to see on the table when you sit with family, because it’s the work of the whole family to make it from seed to table. The third thing is that for some reason, for myself, being able to cook her food instills a sense of connection to the past. It’s an honor to be cooking it, and a responsibility in presenting it.”

While the food for the meal will come from the work of Lewis, the wines are from Mr. Mack. André is African American, and I am not, but our culinary backgrounds appear to have more in common than either of us did with the food with which the young Edna Lewis lived every day. He was largely raised in Texas, yet grew up all over the place, a far cry from the countryside of rural Virginia that gave Lewis her culinary roots. Wild berry picking was not on either of our weekly agenda of activities; neither of our respective families drank or knew much of anything about food or cooking.

Unlike Lewis, who had a lifetime of lovely food and a deeply-rooted culinary philosophy to share with the world, André and I began working in restaurants really only because we needed jobs. Granted, he started in the dining room and I dove in by working the dish tank, but neither of us got into it with the idea that food service would stick as our vocation. Restaurants, André explained, felt like a diversion, killing time and making some money while he figured out what he wanted to do with his life. Which is how my life was “supposed” to go as well. I took my first restaurant job simply so I could afford to stay in Ann Arbor and avoid moving back home. I didn’t know what would come next but I never imagined I’d spend the rest of my life working with food. Same for André. “Everyone waiting tables thinks that at some point they’ll go on to bigger and better things,” he told me. “Or, they used to think that they were going on to bigger and better things, until they realized that they actually like the food business! Well, I went to ‘bigger and better things’ by getting a job in finance.”

André’s choice probably would have made my mother much happier than my decision to keep cooking did. He took a high-end job in finance. Maybe I saved myself some stress by failing to get where I was supposed to. “But when I got into finance,” André explained, “I missed the instant gratification that you get from dealing with people face to face. I missed that connection with people.” Fortunately for him and for all of us who now enjoy his wines, he had the courage to quit. I admire the way André honored his intuition—it’s not easy to walk away from the identity society says certifies you as a “success.” “I wasn’t really sure what I was gonna do,” he told me. “So in the interim I went back to work in restaurants. And I started watching old episodes of Frasier. And that’s really what gave me the courage to invite wine into my life. Not that I thought I was going to be a winemaker. It was more like, “Hey, you should go into a wine shop. And hey you should look into this and maybe have a glass with dinner.” Wine, it turned out, was about to become his way of life. “I’m a Type A personality so when I gravitate to something, I’m all in. I don’t just nibble, I devour. That’s what wine was for me. Everything else in my life is the same way. Chess, horses, basketball…I let things consume me!”

Edna Lewis grew up with good food and cooking, so much so that she said no one ever really taught her to cook; she just knew. André, on the other hand, started learning his craft “late in life.” He was 30 before he really got into wine—about the age at which Edna Lewis was already running the kitchen at NYC’s then-famous Café Nicholson serving folks like Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams and Gore Vidal. “I started to study as a sommelier,” he said. “The place I was working wasn’t known as a wine place so I got into sommelier competitions to see where I stood up against my peers. I’m highly competitive, but, really, I’m more competitive with myself. I wanted to see if I really knew the stuff I was memorizing for the tests. And then I won all these competitions and that got me ready to work for Thomas Keller at Per Se. And there I was working for one of the best chefs in the world, at one of the best restaurants in the world. But then I had this epiphany that that wasn’t going to be ‘it’ for the rest of my life. And that’s really when I got into wine.” He founded Maison Noir in 2007, a year before Edna Lewis passed away.

André and I have very similar views on life, “To be a master of anything is to be forever a student,” he said. “I wanted to live and to learn and the best way I thought to do that was to make my own. I wanted to be an entrepreneur and be more creative, to have more creativity in my life.” A creative and meaningful life of study in anything, is, of course, built upon a philosophy. In André’s case, a philosophy of wine. “My philosophy is always food first,” André said. “To make food-friendly wines. Not just wines that were honest and spoke of the place. And not just wines that weren’t over-adulterated. We wanted to make clean wines that had some acid. Acid is an amplifier. It’s like salt in your food. It’s not really the actual flavor you’re tasting but without it the other flavors don’t come out well. That’s what really interested me.”

André and I also have a high affinity for t-shirts. André designs and sells his own. “I was always a t shirt guy,” he told me. “Chef Thomas Keller had a rather keen sense of humor and it was great to see how he wove it into the menu. When I worked at Per Se they made t-shirts for the staff any time there’s something going on. When you saw someone wear the shirt you knew they worked there. I wanted to do it, too, for the wine.” They’re part of André’s efforts (successful, I’d say) to infuse some humor and casual context into a wine world that often takes itself awfully seriously. Like Randall Graham at Bonny Doon, he brings intelligence and wit to his work, all the while making really good wines. He’s even designed what might be the world’s first culinary-centric coloring book. He’s anything but mainstream. Building on that sense of fun and deeply held philosophy, André works very hard at his wine making. You can see the results in the awards he’s won. Best Young Sommelier in America in 2003, the first African American to win that distinguished honor. His wines are on the lists of many of the country’s best restaurants.

“What are two or three things that you wish more people knew about wine?” I asked André.

“You know…the biggest thing that wine is intimidating for all the wrong reasons! I think you know people are drawn to wine because of its sophistication. But for me it’s just a beverage… it’s not a meal unless you have wine. The further it gets from the vineyard the snootier it gets! But winemakers are farmers. In that sense, it takes a lot of the pretense that surrounds wine out of the picture. When you realize the winemaker is just a farmer…the whole thing is a lot more down to earth.” And? “I wish more people would try more things with wine. You know that saying, variety is the spice of life. People are so set in their ways with wine. I just want people to keep trying them. That’s what makes it all great. I want the guy who just wants to have a cheeseburger every night to have a glass of good wine with it.”

André was speaking my language. “For me,” he went on, “it’s just taste, taste, taste! The biggest thing is that we want people to know is that you’re an expert in your own taste. You taste and you know whether you like it or not. You don’t need an expert to tell you what you like. You like what you like. Be confident in that.” To Amin Maalouf’s well-made point about each of us having multiple identities,André Hueston Mack is a self-taught artist who also has a graphic design business. Just your typical African-American winemaker, t-shirt wearing, award-winning sommelier, graphic designer, coloring book creator.

Dinner with Andre and Edna

To honor the work of these two exceptional individuals, to celebrate the significant contributions made by African-Americans to what we know as “really good American food.” And wine. If you feel as positively and as strongly as I do about the import of recognizing that contribution, I hope you’ll join us at the Roadhouse for a dinner with André, featuring Edna Lewis’ recipes. Even if you can’t make it that evening, I hope that you’ll consider the lesson that their meaningful lives have left with me. Frances Lam, writing lovingly about Lewis in the New York Times closed his piece with this story:

“It has been almost 10 years since Lewis died, 40 since she published The Taste of Country Cooking. Who carries her torch? There are many calling for seasonal, organic eating, but who else has been afforded the iconic position Lewis held, to keep showing us the rich history and influences that black cooks have had on American food?…Is America looking hard enough for the next Edna Lewis?” It’s a question that has weighed on Toni Tipton-Martin (who came to Ann Arbor to speak at one of our earlier African American foodways dinners back when her book was coming out) for years, as she pored over hundreds of African-American cookbooks to write The Jemima Code. She got to speak to Lewis at a food writer’s event and, while still in awe of her, steeled herself to tell her that she was not the only one. ‘’I told her that I wanted to tell the world that there were more women like her than just her,’ she said. A while later, Lewis sent her a letter, written on the same kind of yellow legal pad that she used to write The Taste of Country Cooking. ‘’Leave no stone unturned to prove this point,’’ she wrote. ‘’Make sure that you do.’’”

For me, Miss Lewis’ last point, might really be the message of this meal. Because although Edna Lewis was amazing, and André Hueston Mack is so today, I would argue that the world is filled with equally amazing, unique individuals who society tends to pass right by as if they didn’t exist. Millions of them. They are, as poet Gary Snyder said so beautifully, “like sages growing melons in the mountains.”

For me, the point of the evening might well just be that social stereotypes, bias, stigma, quietly placed roadblocks, and a failure to understand unspoken beliefs, has left so many people—just as special as Miss Lewis or Mr. Mack—behind. They may, from afar, look like just another kid on a street corner or a college sophomore lost in their life, but if we get up close and take time to really look, and to listen, to look past the social stereotypes in which society attempts to imprison them, we’ll find their wisdom. While this dinner is clearly a tribute to its two “guest stars,” I’d really rather frame it as being in honor of the melon-growing sages all around us, in the African American community, in the Ann Arbor area, and in the world at large.

Join us on the evening on January 30—two weeks before the anniversary of her passing—to celebrate her work, the wines of André Hueston Mack, and the marvelous, intricate, creative and exceptional culinary contributions of the African American community.

Make a reservation for our 13th Annual African American Dinner here.